I asked this a few weeks ago via social media and many people had some…

Choreography 101: Improv

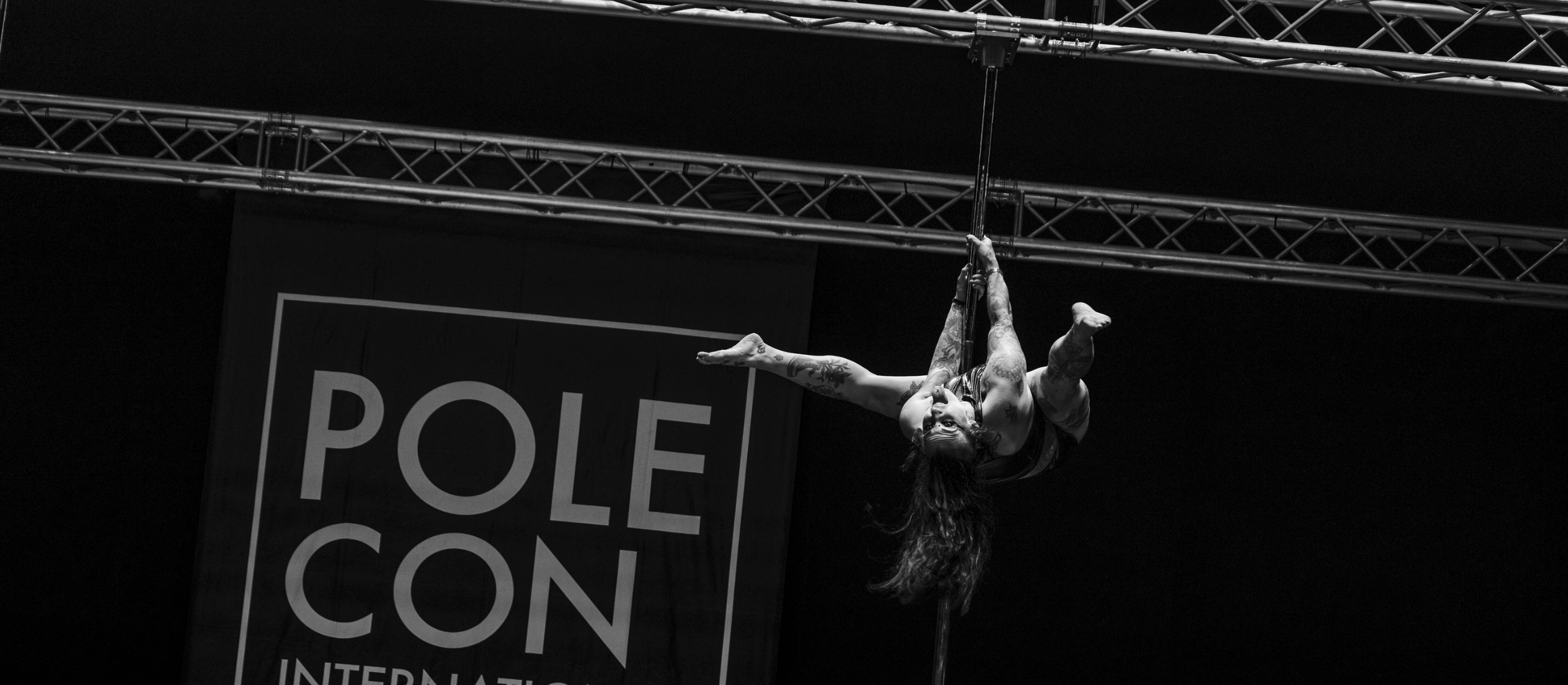

Scene: After a recent showcase.

STUDENT: That was so amazing! Everyone did such a great job!

ME: Are you going to perform next time?

STUDENT: Oh, no. I don’t know how to choreograph.

The preceding scene has happened to me on multiple occasions. And while one does not need to be a choreographer to perform, pole dancing lends itself readily to individual expression. It makes dancers want to express themselves. Choreographing is as much a learned skill as dancing. Some people might be more naturally inclined toward it, but everyone can learn to do it.

Let’s start with the basics:

Learning to improv is the first lesson in learning to choreograph. Improv is shorthand for improvisation, which means to create something in the moment without any planning. This might seem like the antithesis to choreography, but it’s actually the foundation. Choreography (planned movement) evolves out of improv.

One reason improv is important is because it prepares dancers to actually dance. Knowing how to perform a technique is only so useful if you don’t know how to connect it to something else. Improv helps dancers find organic ways to transition between techniques.

Many people come to pole dance with no prior dance training; this can make them feel anxious or awkward when trying to improv. But not to worry, because improv is about exploring movement rather than mastering technique. For example, how many ways can you find to raise your arm? (Shoot your arm straight up, fingers outspread, like you know the answer in class; sweep your arm up like you’re rubbing a velvet curtain with the back of your wrist; scoop your arm up like you’re splashing someone else with water, etc.)

To test your improv skills try this exercise: Pick a piece of music (3-5 minutes long), press play, and move. Do keep moving the entire time. Don’t plan what you’re going to do next, just do it. Do listen to what your body feels. Don’t stop to assess how well or poorly you performed a certain technique. Do pay attention to how you transition. Don’t repeat a technique immediately (remember: this is improv, not practice). Do have fun.

When the music finishes, that’s when you stop and assess. Some questions to ask yourself:

- Did you move with the music or independently of it?

- What are the movements that felt natural to you?

- Which body part(s) initiated movement most? Least?

- Did you stay in one place or move around the space?

Music: If you’re the type of dancer who moves with the music, improv is probably easy for you. You’ll want to pick music first and let the choreography evolve from it. However, if you find yourself stuck, keep the choreography but try dancing it to different music so that you can uncover new ways to develop the movement. If you’re the type of dancer who moves independently of the music, improv might feel like pulling teeth. You can try choreographing in silence first and then finding music that supports your movement. Trying several different styles of music can help you see what supports or distracts from your movement.

Movement: When you improv, you’re most likely to use movement that feels comfortable and familiar to you. Were these movements slow, sensuous, round? Fast, sharp, angular? Fluid or staccato? Small or big? Tight or loose? Happy or sad? There is no right or wrong answer; recognizing your movement style is critical to learning to choreograph. How you move as a dancer is reflected in how you think as a choreographer. Knowing your habits and preferences will help you grow beyond them to find movement that’s new to you.

Body: Within your movement repertoire is the preference for certain body parts. Dancers who prefer to be gestural focus on extending their limbs, using their arms and legs to initiate movement. Postural dancers prefer to work from the center out, originating movement in their hips, chest, or spine. Again, knowing what your natural default is can help you move outside your comfort zone.

Space: Are you a wanderer or a homebody? When you improv, do you explore all around you or do you enjoy staying put? In pole dance, it’s very easy to park yourself in one place, moving vertically but not beyond your eight-foot radius. Again, there’s no right or wrong, but being aware of what you are doing will help you make conscious decisions in your choreography.

Once you know your preferences, you can choose to work with them or against them. For example: If you tend to stay in one spot, you can try marking out a small space and experiment with what you can perform while staying within those confines (for inspiration, take a look at Martha Graham’s “Lamentation”). Or, you can force yourself to move through your entire space by making sure you interact with each corner of your room. Taking movement to extremes helps you push your boundaries.

There is no secret formula for making a great dance. The choreographic process is one of experimentation and evolution and it is almost never linear. Improv helps explore how different movements fit together in different ways, and eventually those pieces become something bigger — something that looks a lot like choreography.

Latest posts by April Rayne (see all)

- Choreographic Devices - July 21, 2017

- Choreography 101: Improv - July 7, 2017

- Quiz Time!: What’s Your Pole Style? - April 21, 2017